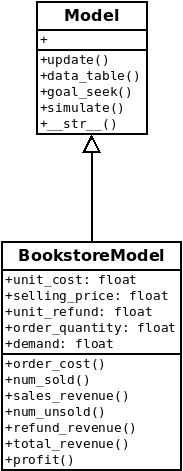

Now that we've got a critical mass of "proof of concept" code, let's figure out how to structure our project and create a deployable package. In addition, let's rethink our OO design and add some much needed documentation to the code.

Python packaging basics¶

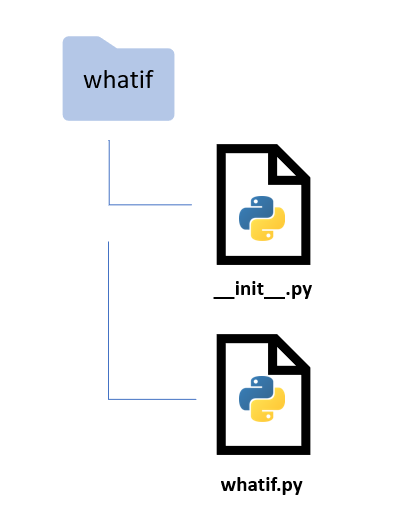

What is a Python module? What is a Python package? A simple way to think about it is that a module is a Python file containing code and a package is a folder containing Python files and perhaps subfolders that also contain Python files (yes, there are many more details).

There are tools for turning such a folder into packages that can be uploaded to places like PyPI (Python Package Index) or conda-forge (if you've used R, think CRAN) from which people can download and install them with package installers like pip or conda.

If you are new to the world of Python modules and packages, a great place to start is the tutorial done by Real Python - Python Modules and Packages - An Introduction. After going through the tutorial you'll have some familiarity with concepts needed in our tutorial:

- Python modules and how Python finds modules on your system,

- the different ways of importing modules,

- exploring the contents of modules,

- executing modules as scripts and reloading modules,

- Python packages, the

__init__.pyfile, importing from packages, and subpackages.

Other good high level introduction to modules, packages and project structure are:

Of course, one should also visit the official Python Packaging User Guide (start with the Overview), especially with the ever evolving nature of this topic. See this recent series of posts on the State of Python Packaging for an "exhausting (hopefully still kinda high level) overview of the subject".

With a basic and limited understanding of Python packages, let's get to turning whatif.py into a package.